GREENLAND: MIGRATION

Directing: C+

Acting: B-

Writing: C-

Cinematography: B

Editing: B

Special Effects: B-

Watching Father Mother Sister Brother and Greenland: Migration back to back is quite the one-two punch of bad movies—wildly different in every conceivable way, except they are bad. Oh sure, they both have their few barely-redeeming elements—again, in completely different ways—but the unredeeming qualities easily weigh them down. I wonder how many other people in the world have watched these two particular movies right after each other? Surely it’s just a small handful. Well, I’ll say this much for Greenland: Migration: at least it kept me awake.

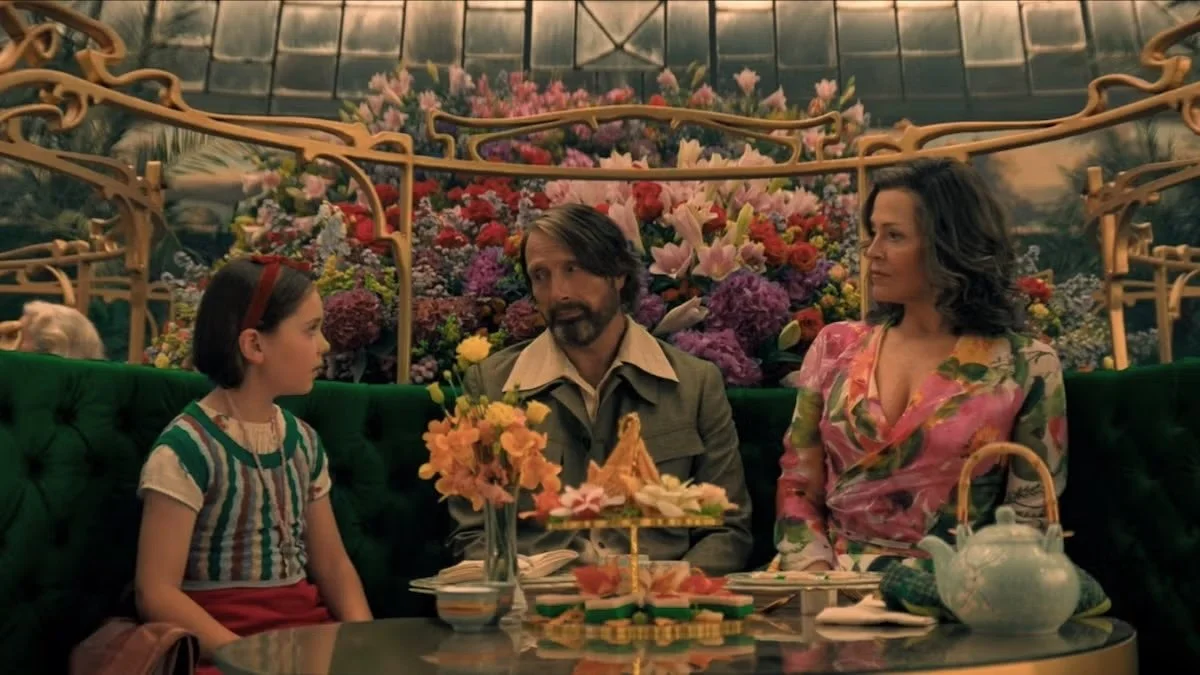

I’m dropping the “2,” by the way, because that’s how the title card reads in the film itself. Posters and promotional materials are listing it as Greenland 2: Migration, which I don’t understand, because the two words together and unbroken actually work as a phrase, as well as a direct reference to what happens in the film. It’s arguably the only sensible artistic choice made in the final cut. And now, our hero, John Garrity (Gerard Butler), his wife, Allison (Morena Baccarin), and their now-15-year-old son Nathan (Roma Griffin Davis—not the same actor who was in the first film) are forced out of the Greenland bunker they’ve been living in for the past five years by tectonic plates causing earthquakes that tear it apart. Over the course of this film’s 98 minutes of utter preposterousness, they make their way to Southern France, where they understand an impact crater has somehow become a shield to all the storms and radiation and is lush green with life. Nobody talks about how safe this spot is from more meteors, by the way.

We’re meant to feel for this family undergoing harrowing hardships, but honestly, all things considered, John Garrity is leading a straight-up charmed life. Oh sure, he barely escapes a tsunami that we see obliterate what’s left of Greenland (a visual high point in the film), and he encounters marauders, and he nearly falls to his death in a somehow dried-up English Channel, among other things. But also, nearly every step of the way, the Garritys encounter some kind-hearted soul willing to help them out. Someone is always coming along to help them through whatever scrape they’re in, far more than would ever realistically occur in an actual post-apocalyptic wasteland. But we’re not here to think about that, we’re here to be entertained.

They even pick up a very pretty teenage French girl along the way (Nelia Da Costa), and director Ric Roman Waugh (Angel Has Fallen) is surprisingly subtle about how we definitely need these two beautiful teens to start making beautiful babies. Maybe part 3 in this franchise can be called Greenland: Copulation. It wouldn’t be any less ridiculous than anything we see in Migration, which is easily the dumbest movie I have seen in recent memory.

There’s a peculiar quality to Greenland: Migration, that almost saves it, this sense that it barely takes itself too seriously. This is not a movie that is “in on the joke,” which in a way makes it more fun. There are plenty of laughable moments that are not intended to be. There’s a death scene in which a callback to an earlier scene is used, where Nathan recites a prayer he previously questioned. Never mind that in the scene being referenced, John is burying the body of an expendable character who had been in the car with them, and I just thought: These guys just dodged a bunch of meteors. I would not be wasting time burying a body. To say this film is filled with lapses in logic would be an understatement. In another scene, when John has run out of bullets defending his family against marauders, Allison comes to the rescue with her own gun. The thing is, we have only ever seen John get handed a gun, so where the hell did Allison get hers? I guess she pulled it out of her ass. She never seemed uncomfortable sitting on it, so color me impressed.

I should note that I am hardly the only person being much harder on Greenland: Migration than I was on the original Greenland, which was originally scheduled for release in 2020 but later released on VOD and which I did not watch myself until the VOD price went down, in February 2021. At that time, most of us were still working from home if we had jobs where that was possible, covid was still an actively scary thing, and a movie like this provided welcome escapist entertainment, even if it was a bit darker than most disaster movies. It didn’t hurt that it was relatively well paced and was better than most might have expected, particularly on a $35 million budget.

Well, Greenland: Migration had two and a half times the budget, and it is markedly worse. This time, it isn’t better than expected—it quite squarely meets expectations, and that’s not really a compliment. Gerard Butler pivoted into a full-time career of these B-movie disaster or action vehicles, several of which have actually been fun on their own terms, but we’ve reached the point where we’re getting diminishing returns even in that context.

So here’s the key difference between Greenland and Greenland: Migration. The first film used its special effects sparingly and effectively, and this film leans so much harder into the effects that their still-limited budget is even more apparent. This could have been a compelling survivalist drama if the script weren’t so deeply stupid, which means that even with what tools they had available, they could have at least entertained us with more thrilling set pieces. The greenland tsunami that we see is very early in the film, and the most thrilling sequence in it. It’s all downhill from there. Or rather, across the Atlantic Ocean, through a flooded Liverpool and a dried-out English Channel (someone explain this to me), and across war-ravaged France from there. There is a meteor shower that recalls the coolest action in the first film that’s relatively thrilling, if brief.

But in the end, something so dumb occurs that I covered my faces with my hands while saying “Oh my god.” This film has an earnestness that has no self-awareness, which makes it amusing in its way. I laughed several times. And now I can check this one off my list, and never watch it again.

I am stunned too. By how dumb this is.

Overall: C+