NIRVANNA THE BAND THE SHOW THE MOVIE

Directing: B+

Acting: B

Writing: B

Cinematography: B+

Editing: A

Special Effects: B+

Here’s the burning question about Nirvanna the Band the Show the Movie: what if, like me, you watch this film having zero familiarity with the Canadian TV show on which it was based, Nirvanna the Band the Show, which aired on Canadian premiere network Viceland 2017-2018; or the web series that was based on, Nirvanna the Band the Show, which was made 2007-2009? Does this movie even work for such audiences? The answer is an emphatic yes, and surprisingly well at that.

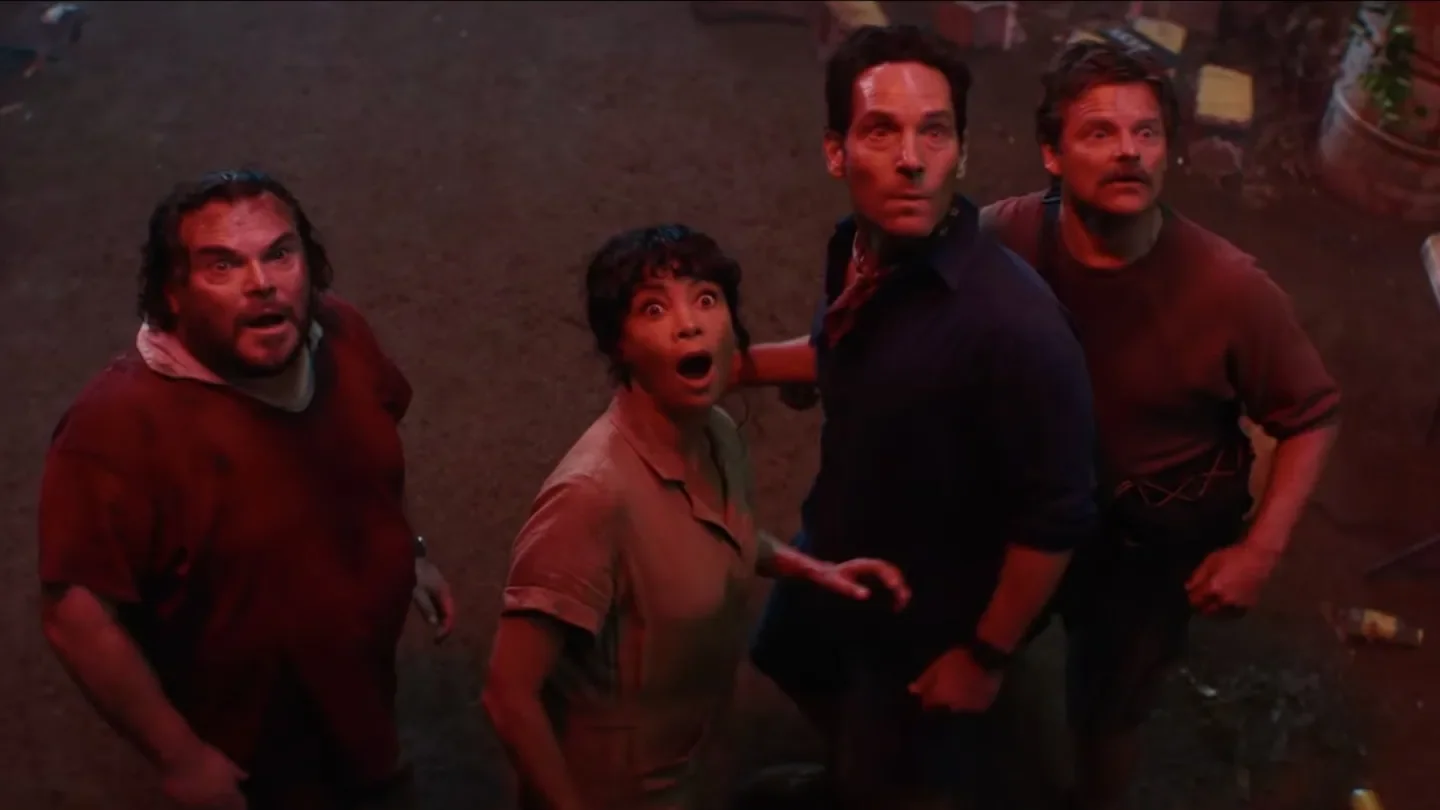

I suppose it might work better for audiences familiar with these earlier works, but I don’t know if it’s by that wide a margin. I had a great time with this movie, which blends old and new footage so seamlessly I kept wondering how the hell they did it. There is a sequence in which Matt Johnson and Jay McCarroll, playing fictionalized versions of themselves (as they did in the previous iterations of the show), go back in time 17 years to 2008 and encounter their younger selves. None of this looks like a special effect; none of it looks like digital de-aging—just looking at the screen is enough to convince you this is actual footage of these two from 2008. I had to find a current YouTube video to learn that not only did they indeed use original video footage from 2007 to 2009, but everything you see in this film was culled from the cutting room floor of those original web series episodes—everything you see here, even if it’s 17 years old, is something never seen before.

As far as I can tell, the series never used time travel as a plot device—this is something new cooked up for the movie, and how they tied the new footage together with the old. They use well-used plot tropes that make no sense upon close examination, which is clearly part of the point. In fact, it lifts so many plot elements from the Back to the Future series that the film is legally regarded as a parody, which allows them to get away with a lot. In this film, Matt creates a fake “flux capacitor” for their RV, which then magically works exactly the same way it does in Back to the Future thanks to short circuiting after he spills 1990s Canadian fruit drink Orbitz all over it. (It’s the last one of a case they’ve had for years. Who could never make a case of favorite discontinued drink last a decade and a half? This movie is very unrealistic.)

They wind up in the year 2008—specifically in Toronto, where the series were filmed. It didn’t even occur to me until later that all the establishing shots of the urban environment indicating it’s 2008 would likely also have just been pulled from old footage from the time. This includes things like a movie poster for The Dark Knight or other pop culture references. As part of the present-day Matt and Jay navigating 2008, there is one pretty hilarious scene where Matt goes into a movie theater playing The Hangover. (That film was actually released in 2009, but let’s not quibble.) Matt witnesses the scene in the film that features the line “Paging Dr. Faggot”—one of several things in that film that have no aged well—and it’s when Matt notices the entire audience finding this hilarious that he realizes something is amiss. It’s worth noting that a film with no queer content otherwise makes it a point to highlight how awful it is to use that language regardless of context; I was really happy to see it contextualized this way, even contextualized as humor (the humor being that he had gone far enough back in time that average people thought this was okay).

There are so many references to the Back to the Future franchise, in fact, that they go back in time, return to a present day that’s been altered, and then go back in time yet again to fix the mistake—this means they reference both the first and second Back to the Future films. And I haven’t even mentioned the mockumentary style, a whole lot of it shot guerilla-style with unspuspecting, real people on the street. This seems to have been largely the premise of Nirvanna the Band the Show all along, and it works here much better than, say, in Borat, which exists to expose regular people’s prejudices through the use of “ironically bigoted” humor. That shit never sat well with me, and there is none of it here. Even the presence of a queer epithet exists only to show how much progress has been made, rather than having the protagonists pretend to be homophobic themselves.

This gets back to how much of the film had me wondering how they pulled it off. Very early in the film, Matt and Jay attempt a publicity stunt in which they parachute off the CN Tower. A lot of this is clearly staged, but even here we see people around them who seem to have no idea what’s really going on—and it sure looks like there was actual footage shot atop that building, in one case all the way to the tip-top of its antenna, a spot not accessible to the public. Is it possible that this show is just so beloved to Canadians that they managed to get access for filming? Some of this footage is astonishing.

Clearly the most impressive element of Nirvanna the Band the Show the Movie is its editing, not just with present-day footage combined with footage from the late aughts, but with narrative (or, as was mostly the case, improvised) footage of the actors interacting with regular people. I would recommend this film on that basis alone. But, there would also have to be a VFX element to this, particularly when old and younger Matt and Jay are in the same sequence together (using clever narratives where neither of their younger selves fully register that their friend looks 15 years older—there’s a lovely line about how you don’t notice your best friend growing older). There are also the scenes in which the RV-turned-time-machine does its time jumps, with effects that look exactly like those used in Back to the Future.

What I find most impressive about Nirvanna the Band the Show the Movie is how lovable the characters are, and how easily invested you get in the outcomes of their stories, even if you haven’t seen the series it’s based on. I don’t know much about how “Nirvanna the Band” came to be, as there isn’t a single reference in this film to the Kurt Cobain-fronted band, and I have no idea whether there ever was in the series; I can only assume this was itself a joke, this duo who call themselves “Nirvanna the Band” but make music that sounds nothing like Nirvana. It makes for a fun, if misleading, expansion on the series title. I have a friend who was a huge Nirvana fan and when I first told him I had seen this film, he clearly thought it must have been some amazing documentary about the grunge band. Nope, not even close.

I mean, it is in the documentary style. There is a lot of inconsistency regarding how the guy holding the camera follows Matt and Jay around without being noticed by key people in certain scenes, not to mention a documentary crew actually traveling through time with this duo, and even keeping tabs on the two of them when they have conflict and separate. But as I already indicated, plot logic is nowhere near these guys’ top priority here. And the overall experience is so much fun that anything you might want to nitpick is incidental. Given all the elements of how it was put together, the fact that this film exists at all is practically a miracle, and how funny it manages to be is icing on the cake.

Matt Johnson and Jay McCarroll pull an extension cord connected to the top of the CN Tower in Nirvanna the Band the Show the Movie.

Overall: B+