AVATAR: FIRE AND ASH

Directing: B+

Acting: B+

Writing: B-

Cinematography: B+

Editing: B-

Special Effects: A-

I think James Cameron wants the Avatar films to be the 21st-century equivalent of the Star Wars films—a modern mythology, with the same cultural impact as well as staying power. (Some might argue that Marvel already achieved this, but their moves are not going to have the same staying power.) Cameron is such a directorial megalomaniac, he’s probably convinced these films already have that status. He would be wrong.

To be fair. it had long been widely understood that it is a mistake to underestimate James Cameron. But these movies can only run on their own steam for so long. Avatar was a monumental technical achievement in 2009, and was worthy of its Best Picture nomination (although it would have been a crime had it won). The same could be said, actually, of Avatar: The Way of Water, the sequel Cameron took 13 years to make because he was waiting for technology to advance enough so it could achieve his aims. And it’s worth repeating that The Way of Water was so stunning on a visual level, it arguably moved visual effects forward for the entire industry in a way no other film has since Jurassic Park.

So here is where we run into Avatar: Fire and Ash, only three years after the last one—usually a pretty standard duration between films and their sequels, but we all know the Avatar franchise is a different beast altogether. And the criticisms of this film as being entertaining but repetitive are fundamentally valid. With one notable exception, the characters are all the same as they were in the last film, and the things that happen onscreen offer us very little that’s new. Okay, there are some very cool new Panodorian creatures, including giant floating beasts that pull ships for travel, and vicious squid-like creatures that live in the oceans.

None of them feature as actual characters, though. The only beasts who do are the Tulkun, the highly intelligent whale-like creatures that featured prominently in The Way of Water, and do again here. And so does Quaritch (Stephen Long). And so does Captain Mick Scoresby (Brendan Cowell), who—spoiler alert!—did not die in The Way of Water after all. I walked out of this movie saying that if this series has taught us anything, it’s that any onscreen “death” cannot be trusted. More than one character in Fire and Ash meets an end that is one way or another is left ambiguous. But even if it were unambiguous, would it matter? This is a world in which “sky people” (humans from Earth) can be transformed into Na’vi and there can be an Avatar-maculate conception, after all.

Side note on the Tulkun whales: who the hell does their piercings and tattoos, anyway?

All of this is to say: if you’re looking for a 2025 blockbuster with endless opportunity for nitpicking, I present to you Avatar: Fire and Ash. I’ve barely scratched the surface here, but it’s worth mentioning that this has a franchise-record runtime of three hours and 17 minutes (exceeding The Way of Water by five minutes), and it is far less successful than its predecessor at justifying its own length. The Way of Water is easily broken up into three parts, the middle of which is world-building that easily wowed audiences; the last of which is a truly thrilling succession of action sequences. Fire and Ash attempts to building on that foundation, but does far less world-building, overindulges on action sequences, and at the sacrifice of character development.

To be fair, I was still perfectly happy to have gone to see this movie, as many of its action sequences are indeed thrilling. The visual effects are nearly as stunning as they were in the previous film; the inevitable downside to this coming out only three years later is that it’s unable to offer us anything truly novel on that front. The visual effects are the reason to see any of these movies, though, and they are what sets these films apart from others that use 3D as a cheap trick. Cameron knows how to make 3D worth the effort, and this is an extremely rare case in which I was also thrilled to see it in that format. That said, while the creature and Na’vi designs are exceptional, there are still moments when characters leap long distances and don’t quite move the way they should. It’s very subtle, but still gives them a hint of looking like video game characters rather than a believable character in a richly built universe.

In addition to Quaritch, who is really growing stale as an antagonist in all three of these movies, Fire and Ash does give us one new major villain: Varang (Oona Chaplin), leader of the Ash People, a clan of Na’vi whose forests have been decimated by a nearby volcano. This is a compelling addition to this world, especially the idea of warring clans on Pandora whose beefs actually have nothing to do with the Sky People. Except the Ash People’s motives, and especially Varang’s, are never clearly defined, and as a people they are given far less nuance than the Na’vi. At least we can understand the Na’vi as a narrative example of cultural appropriation. The Ash People are just angry and sadistic, and read a little too much like so-called “savages” of the Old West who are thought to commit unspeakable horrors against outsiders for no discernible reason.

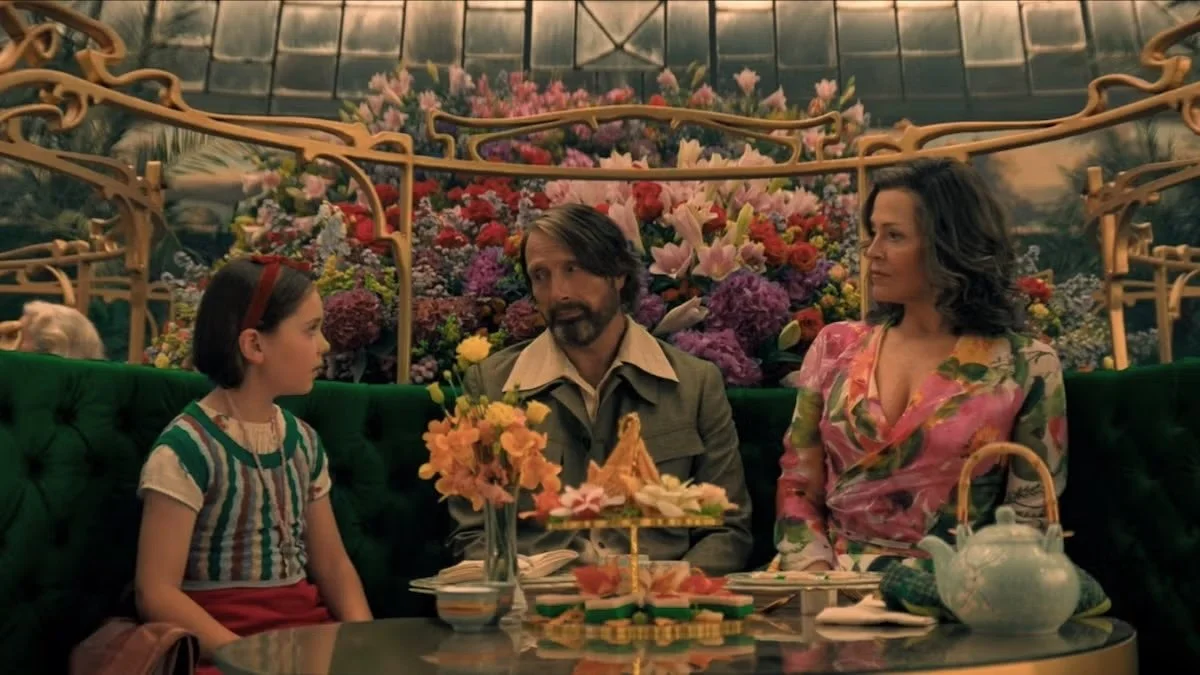

I wish Varang had more depth as a character, and certainly more autonomy. Here she’s just hungry for the power of Sky People’s military guns, and that hunger is easily manipulated by Quaritch. Thank Eywa we have the likes of Neytiri (Zoe Saldaña) and Kiri (Sigourney Weaver, a 76-year-old woman again doing motion-capture as a teenager) and Ronal (Kate Winslet) to serve as women characters who actually have some dimension. At least Fire and Ash passes the Bechdel Test.

Most of the time in Fire and Ash, though, there are just battles raging. One after the other, and this with multiple subplots that don’t all feel necessary. Maybe Cameron feels all of these narrative threads are vital for what’s to come in future sequels, but I’m not sure how much that matters. Kiri’s power to lock in with Eywa stayed mysterious through all of The Way of Water, and gets some further expansion and explanation here—some of which is legitimately dumb. I suppose that could be the tagline for Avatar as a franchise: “great action epics, some of which is legitimately dumb.”

Fire and Ash does bring Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) back around to his status as “Toruk Makto,” the legendary leader who unites the clans—his Leonopteryx, the giant bird-like creature he rides, is a loyal friend who is to a degree a creature-character in these films, as are, to a lesser degree, the banshees ridden by all the other Na’vi. None of this changes the problematic trope this title represents. When we hear the line, “Toruk Makto is coming!”—what I heard was: “White Savior is coming!” (Just because Jake was transformed into a blue-skinned human/Na’vi hybrid does not change what he represents in the narrative.)

And yet. And yet! This is how it is with all Avatar movies: they are riddled with flaws, particularly in the writing but also increasingly in the plotting and even the editing—but the things that are actually great about them make the flaws easier to overlook. Is that right? Perhaps not. Does James Cameron even understand a nuanced discussion of these things? I have my doubts. Is the man still a master at delivering mesmerizing entertainment? Absolutely. There is no question that I was on the edge of my seat and dazzled by Fire and Ash a whole lot of the time. I can’t say I was ever bored, in spite of the bloated runtime. What still defines this film more than anything, however, is this franchise’s diminishing returns. We can only hope that Avatar 4 will offer us something genuinely new, but being the fourth film in a series makes that a pretty tall order. It may be that we underestimate James Cameron at our own peril, but it’s starting to feel like he’s getting tired.

Overall: B