Below are the ten most satisfying and memorable films I saw in 2025:

10. Hard Truths A-

10. Hard Truths A-

This is the first of three films on this year's list that are technically 2024 films but did not get released in my local market until 2025—and I refuse to ignore an excellent movie just because it's only technically from the year before. This film, about a deeply depressed and obstinately, aggressively negative woman played by Marianne Jean-Baptiste, is packed with stellar performances—and Jean-Baptiste was criminally robbed of an Oscar nomination. Pansy, the main character, is surrounded by a cast of family members, particularly a husband, a sister and two nieces, who love her and want to be there for her, but are faced with the constant challenge of Pansy making that difficult for them. The amazing trick here is how a woman with such a horrible demeanor and attitude can be rendered so empathetically.

What I said then:

Mike Leigh isn’t exactly known for movies with much in the way of uplift. He makes movies about deeply unhappy people, but with a curious knack for sprinkling in truly funny bits here and there—even in the case of Hard Truths

. Still, this film does end on a truly downbeat note, with the suggestion that people like Pansy don’t tend to change. Not without treatment, anyway. But this film was something I found to be an emotionally cleansing experience.

9. Weapons A-

9. Weapons A-

I'm not by default one for horror movies, but Zach Cregger's previous film,

Barbarian, was an undeniable blast, so I was all about seeing

Weapons—which is a rare case of a sophomore effort being even better. Both movies are best seen going in blind, with no knowledge of what's going on whatsoever, except with the promise that they are by turns terrifying and hilarious. Acknowledging that this idea makes it pretty difficult to market a movie, all you can do is the best you can. My greatest hope is that one day Creggor can become so well-established in the industry that he can get by with trailers that amount to little more than glorified teasers. A bit disappointingly, his next project is a film adaptation of video game

Resident Evil, but these two movies have proven his ability so well that I will likely see that film based on Creggor's name alone. I'd almost certainly never bother with it otherwise.

What I said then:

There is no allegory or metaphor to be found here; Weapons

is simply a magnificently structured and cleverly written horror story, the kind that makes you remember how exhilarating it can be to go to the movies—especially with a crowd of people.

8. Black Bag A-

8. Black Bag A-

Maybe the most memorable pleasant surprise of the year, I totally expected to enjoy

Black Bag as a serviceable spy thriller, but not necessarily a particularly memorable one—until it proved itself to be so. Michael Fassbender and Cate Blachett have a crackling energy as married intelligence agents George and Kathryn, and when George is tasked with secretly investigating whether Kathryn has betrayed her country,

Blag Bag doubles as a tense marriage drama. The film works incredibly well as both spy thriller and marriage drama at the same time, a delicate balance seamlessly achieved by director Steven Soderberg and writer David Koepp. An incredibly written and staged dinner party scene alone makes this movie worth the time.

What I said then: Black Bag

is intrigue at its finest, a feast of sleek production design as a backdrop for a mystery both complex and concise. Not a moment is wasted in this movie, which is so well done, it leaves you wondering why so many other similar movies dwell on their own plotting so pointlessly.

7. I'm Still Here A-

7. I'm Still Here A-

This is the second of the three films on this list technically from 2024, but is so skillfully constructed it would be a crime not to include it. Fernanda Torres is incredible as Eunice Paiva, the real-life wife of Brazilian Congressman Rubens Paiva, who was abducted by the Brazilian military dictatorship in 1971. Eunice, until then not especially engaged in politics or activism, was spurred by this incident into resisting this government, to the point where both she and her eldest daughter were themselves imprisoned without charge and interrogated—her daughter for one day; Eunice for twelve. Eunice's story in

I'm Still Here uses these incidents as a jumping-off point to tell her extraordinary story, as her tenacity in getting answers about the fate of her husband turned her into an activist, and she went to school and became a lawyer. With a rather poignant epilogue featuring Torres's own mother, Brazilian actress Fernanda Montenegro, as Eunice at the end of her life,

I'm Still Here offers a memorable lesson in how oppressive regimes can only strengthen the resolve of those they mean to keep down.

What I said then:

With I’m Still Here

, [director Walter] Salles has created something so straightforward that it doesn’t seem all that profound while watching it. But there is something ingenious about its construction, a subversive thread that is an indicator of the sinister nature of dictatorship, especially when daily life seems basically unchanged for anyone besides those directly affected. This is a film that could not possibly be more timely.

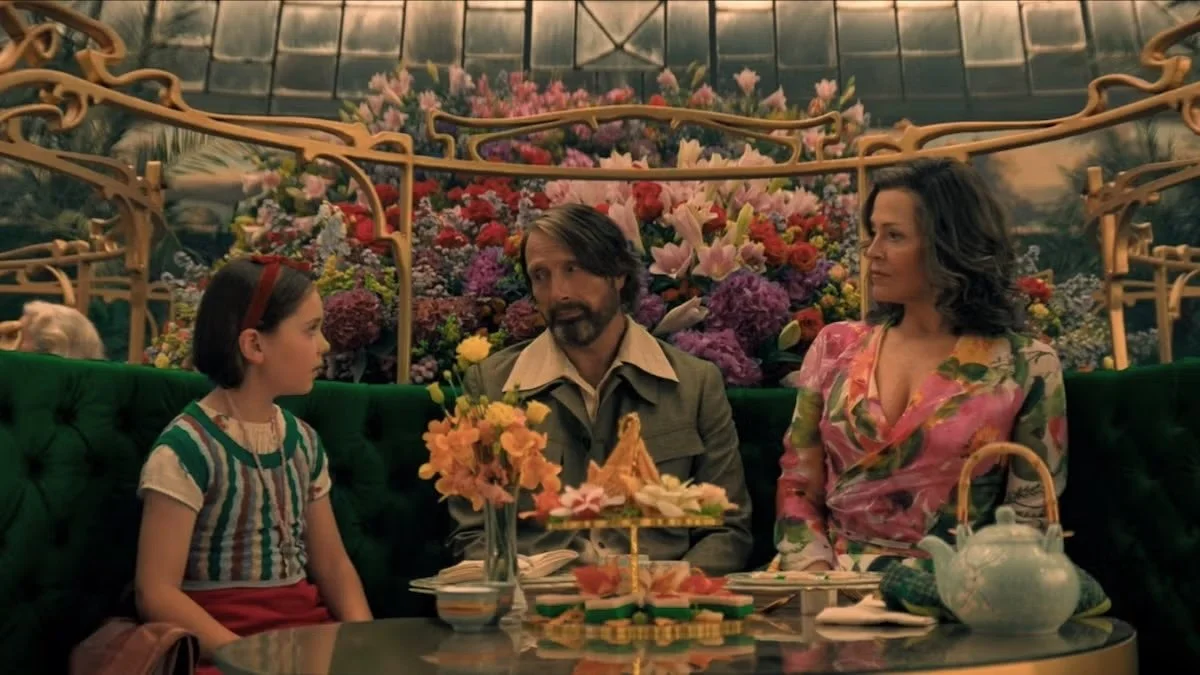

6. Sentimental Value A-

6. Sentimental Value A-

It would be tempting to say Danish-Norwegian writer-director Joachim Trier's films are typically of a piece, but that's only because both

Sentimental Value and his previous film, 2021's

The Worst Person in the World (my

#2 movie of 2022), feature exceptional performances by Renate Reinsve, and are incisive explorations of complicated relationships (one romantic, the other parental).

Sentimental Value has great performances all around, but uniquely nuanced deliveries by both Stellan Skarsgård as a legendary director and absent father attempting to reconnect with his actor daughter late in life in the only way he knows how, and Elle Fanning as the American actress he casts and who tries hard but cannot fully connect to the semi-autobiographical part she's playing.

What I said then:

All of this comes together in a plot that is complex but never difficult to follow, and perhaps may even be a bit slowly paced for some viewers. It’s worth noting that although this is a family drama about two sisters with deep resentment toward their father, there are no histrionics here, no scene made for an Oscar clip. Where other movies of this sort go for familial cruelty, this one leans more heavily into a kind of benign neglect. There’s something about Stellan Skarsgård’s performance, though, that still elicits empathy. Few people can convey subtly tortured interiority like Stellan Skarsgård.

5. The History of Sound A-

5. The History of Sound A-

The History of Sound got mixed-positive reviews overall, a

63 rating on MetaCritic, making it the film with the most-mixed reaction that I still put on my top 10 this year. But this movie really,

really spoke to me—especially as a gay man. I long ago abandoned any attempt at making these year-end lists wholly objective; they never are even if I pretend they are. Why not stop pretending? I'm a gay man, and between a movie like this and a show like HBO's (Crave in Canada)

Heated Rivalry, stories featuring queer joy, and love stories that pointedly reject any focus on queer trauma, tend to leave me deeply moved.

The History of Sound is even a period piece, about two men who fall in love while collecting wax cylinder recordings of original folk songs among small communities of World War I-era New England. It's a quiet and meditative story about yearning, about love and loss only because these two are separated by circumstance rather than tragedy, and it's punctuated by performances of gorgeous folk music. This movie certainly isn't for everyone, but it felt like it was made specifically for me.

What I said then:

I can see how some might lose patience with the pacing in this film, but it would never have worked as well if the plot moved faster. This is the nature of longing, is it not? This is a film that will deeply move those with a mind to be spoken to in the way it’s communicating.

4. The Seed of the Sacred Fig A-

4. The Seed of the Sacred Fig A-

The Seed of the Sacred Fig is technically a 2024 film, and it has a close 2025 comp in the similarly excellent

It Was Just An Accident. Both films' writer-directors, Mohammad Rasoulof and Jafar Panahi respectively, have extremely similar backgrounds: criminalized, imprisoned and exiled from their native Iran for their art. Both films were even filmed in secret. I just found myself slightly more taken with

The Seed of the Sacred Fig, about the strain on a family when the father and husband, just appointed as an investigating judge to approve judgments by his superiors without assessing evidence, suspects his wife and his two daughters when the gun he's been issued goes missing. This all takes place with nationwide protests against the government as an expertly contextualized backdrop, with Rasoulof seamlessly editing in real social media footage into his narrative. While both of these films are deeply effective indictments of the Iranian government, this was what placed

The Seed of the Sacred Fig slightly ahead for me, as the very real stakes at play hit a bit harder as a result.

What I said then:

This film is unusually long, at two hours and 47 minutes, but a lot goes down, it is never slow, and almost none of it feels like wasted time. The run time allows for an illustration of how ideologies can gradually either strengthen or unravel, depending on the person and the circumstance.

3. If I Had Legs I'd Kick You A-

3. If I Had Legs I'd Kick You A-

It's difficult to put into words just how much I loved

If I Had Legs I'd Kick You, given by definitive inability to relate: this is about a woman who feels so unqualified as a mother, taking care of child with a debilitating medical condition and feeling so overwhelmed by it all that she makes a succession of wildly irresponsible choices. But it's a credit to Rose Byrne's extraordinary performance as Linda that I felt sympathy for this character, in a film easily compared to

Uncut Gems in that the entire story is a deeply stressful ride, along which the protagonist's choices are constantly worse than the last. There's just something about the way writer-director Mary Bronstein made this film, which makes it absolutely electric from start to finish, this complex portrait of a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown. A great turn by Conan O'Brien as her deeply uncomfortable therapist is just icing on the cake.

What I said then:

This is a film that ends on the kind of hopeful note that comes with a ton of baggage. I’ll be thinking about this one for a long time, and that’s a good thing. If I Had Legs I’d Kick You

is constantly harrowing, sometimes darkly funny, heartbreaking and uniquely humane.

2. Sorry, Baby A

2. Sorry, Baby A

The first of only two films I gave a solid A in 2025,

Sorry, Baby stands apart as a film about sexual assault that does not follow the countless narrative tropes about the subject established over decades of film history. This treats the inciting incident with all the seriousness it deserves but without actually depicting it onscreen, but also pointedly features characters who move through their lingering trauma with moments of genuine humor as well as their inevitable sorrows, giving them a sense of grace and dimension not often granted. This is an incredibly self-assured feature film debut by director, writer, and star Eva Victor, who identifies as nonbinary and actually manages to incorporate subtle details of gender variance into the narrative of this film in organic ways I have never seen before.

What I said then:

I feel lucky to have Victor take me through Sorry Baby, a film that turns deeply complicated issues and themes into a gem of poignant simplicity.

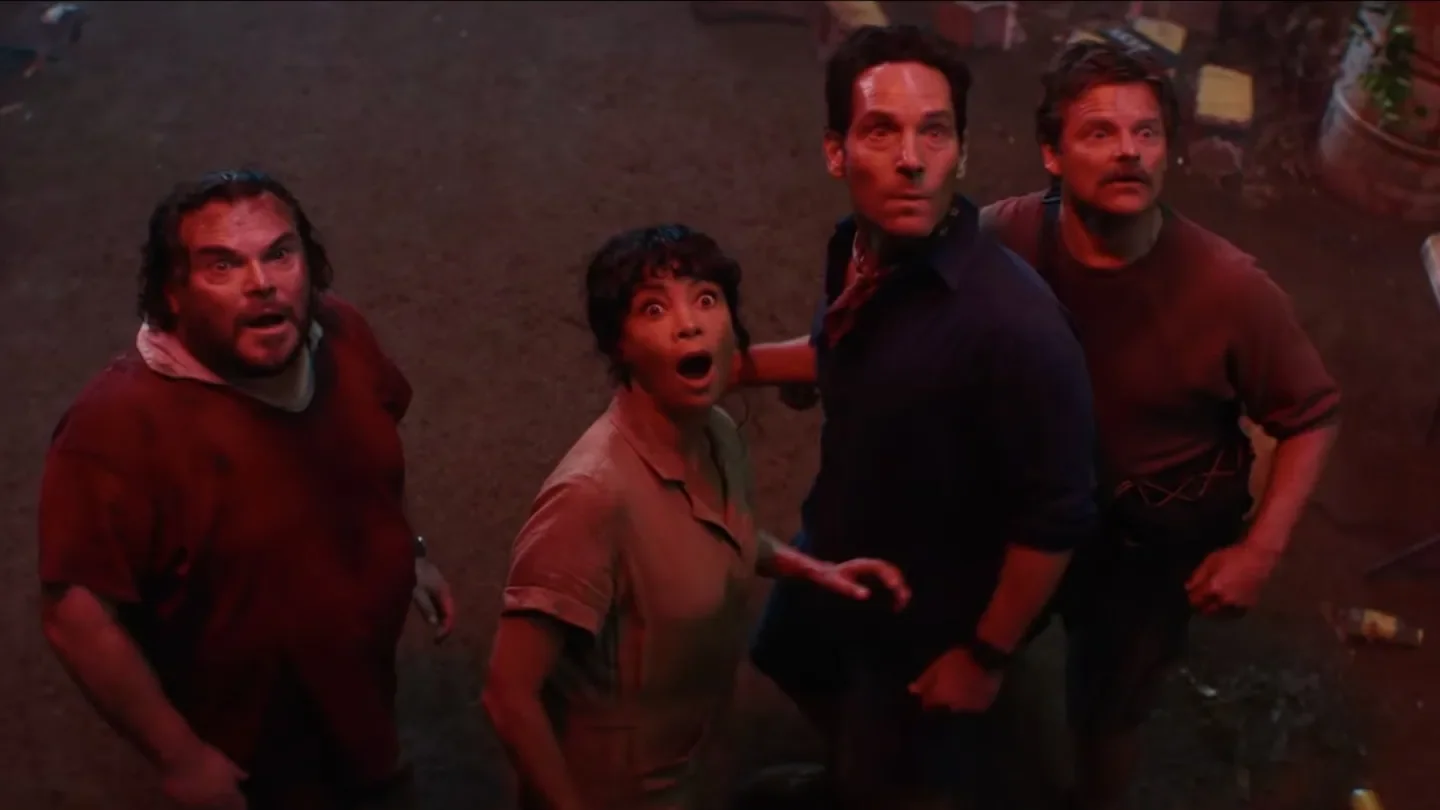

1. One Battle After Another A

1. One Battle After Another A

The movie of the year in every sense of the word—except, I suppose, in the sense of box office, which is not in the least bit relevant to this particular list. Anyone who tries to suggest such a claim is ridiculous can go back to rotting in front of

Superman. We all have our own lanes. And I'm certainly not above admitting a deep bias when it comes to director and co-writer Paul Thomas Anderson, who I have been convinced is a genius filmmaker for two and a half decades. This was the man who first convinced me it was possible to make Adam Sandler tolerable, after all—and

Punch-Drunk Love is in the running as my favorite film of his. In any case, Anderson has been deserving of reward for decades, for many different movies, and there is a developing "it's time" narrative around

One Battle After Another for months now, a fact I can only hope does not result in backfiring its Oscar chances. Because this is classic P.T. Anderson through and through, just with an unprecedented budget, the kind of thing that contributes to endlessly irrelevant debates about its actual "success." None of that shit matters in the face of the fact that this movie about contemporary revolutionaries, using the 1970s actions of revolutionary militants The Weather Underground as inspiration and repositioning them within real-world issues of the first quarter of the 21st century, is a straight up masterpiece. It's propulsive, it's suspenseful, it's hilarious, and it's the best movie of the year without question.

What I said then:

The more I think about One Battle After Another

, the more impressed I am with it. This is the sign of a great movie. I didn’t have the wherewithal to think about whether it was a Great Movie while I was watching it, because I was too absorbed by it. I wouldn’t even say I was blown away by it, per se—and I mean that as a compliment. I was simply invested in every single character onscreen. I only had the bandwidth to reflect on it once it was over, and then, after some time, it gradually dawned on me: that was an amazing movie.

Five Worst -- or the worst of those I saw

5. Nobody 2 C+

5. Nobody 2 C+

Back in 2021, I found

Nobody to be a surprisingly fun romp—a solid entertainment with an amusingly simple premise that turned Bob Odenkirk into an unlikely action star. Its story about a family man who turns out to be a violent fighter getting sucked into a war with a Russian crime boss was not wholly original, but the age and ability of its star gave it a novel quality. I probably should have expected that, by definition, a sequel would have no ability to retain that quality, and would be little more than a retread.

What I said then:

I won’t lie, I had kind of a good time with Nobody 2

. That can happen when you just surrender to what a movie is, in this case a moderately amusing action movie with modest ambitions and zero pretense. That doesn’t make this movie good

, and this is just a rehash of a previous film that barely succeeded on such flimsy merits.

4. Tron: Ares C+

4. Tron: Ares C+

Shame on me, I guess, for thinking I might enjoy the third in a series of films in which I really haven't been crazy about

any of them—and for even bothering to see a movie starring professional dirtbag Jared Leto. I'm not quite sure why people keep thinking the passage of a decade or more somehow results in another entry in this franchise is a good idea; the special effects are kind of fun in their time but quickly dated, and the stories are always completely hollow.

What I said then:

Who even cares about Tron

these days, anyway? Even people who were kids in 2010 are young adults now; young people who were into the original in 1982 are basically retirees in 2025. Predictably, just about everything you see in Tron: Ares is recycled, either from previous Tron movies or other science fiction.

3. The Running Man C

3. The Running Man C

Beware the idea that a film as "a new adaptation" of the source novel as opposed to a remake might alone make it good. And I really wanted this movie to be good. Or at least fun. Instead, it was oppressively clunky, weighed down with awkwardly written exposition, and overlong. Michael Cera shows up and infuses the proceedings with some welcome energy, but this happens far too late to stop the fuse of what was destined to be a box office bomb. (On a budget of $110 million, this movie earned $69 million.)

What I said then:

All of this shit is going in one ear and out the other of anyone watching, who are just there for escapist entertainment in an American cultural hellscape. The very existence of this film is the product of what it’s pretending to be preaching against. It’s worth noting that the one thing this movie does that we haven’t seen much of before is use AI as a plot point, with The Running Man

’s gameshow manufacturing footage that isn’t real in an effort to keep the audience against the contestant—except it’s never addressed as “AI” and only ever declared “not real” in ways, again, we’ve already heard a thousand times. The only thing that could make this entire production—with a budget of $110 million—more perfectly cynical would be to learn that AI was actually used in the making of it.

2. Things Like This C

2. Things Like This C

It pains me to say

Things Like This was the second-worst movie I went to see all year, as I would much rather have seen it succeed. I love the idea of a gay romantic comedy in which one of the guys happens to be fat, except that writer-director Max Talisman

wrote himself into binge-eating cake frosting straight out of a can, at the end of the opening scene. Then it never comes up again. What does follow is a cast whose performances are mostly flat, leads who have no chemistry, and a plot so predictable and unrealistic it's tiresome.

What I said then:

There are many problems with Things Like This

, but the fundamental one is the one-dimensional nature of nearly all of its characters. There’s earnestness here, even occasionally effective sweetness ... but no depth. There is always a sense that there is some depth around, somewhere, but this movie is always out of it.

1. Love Hurts D+

1. Love Hurts D+

This movie, for which I have no love, hurts. Every aspect of it is phoned in, and the script is straight up garbage, easily the worst writing I sat through in a theater this entire calendar year. The direction, the acting, the cinematography, the editing, the action—all emblems of medicrity. The script is utterly worthless. This was the major release for Valentine's Day this year, and such movies are historically hit or miss; this was a miss by a long shot, and it's too bad because Ke Huy Quan absolutely deserves better than this.

What I said then:

It’s difficult to express precisely how bad this movie is. To be fair, there was some talent that went into it—Quan himself is in it, after all, and he’s the one person in it giving a passable performance. But oh my god, the script! Something truly unexpected comes to mind: the old Christian quote about how Jesus answered when asked how much he loves us: “'This much,' he answered: then he stretched out his arms and died.” Time to flip the script, so to speak: that’s how much I hated the writing in this movie. I should really be admitted into a hospital.

Complete 2025 film review log:

1. 1/3

The Fire Inside B

2. 1/9

Better Man B

3. 1/11

The Brutalist A-

4. 1/14

The Last Showgirl C+

5. 1/17

One of Them Days B

6. 1/18

Hard Truths A-

7. 1/21

The Room Next Door B+

8. 1/24

Presence B

9. 1/25

September 5 B+

10. 1/25

Nickel Boys B

11. 2/1

Dog Man B

12. 2/2

The Seed of the Sacred Fig A-

13. 2/6

Companion B

14. 2/9

I'm Still Here A-

15. 2/11

Love Hurts D+

16. 2/13

Paddington in Peru B

17. 2/20

Universal Language B

18. 3/1

My Dead Friend Zoe B+

19. 3/8

Mickey 17 B

20. 3/14

Black Bag A-

21. 3/18

The Penguin Lessons B

22. 3/20

Novocaine B

23. 3/24

The Assessment B

24. 3/28

Death of a Unicorn B-

25. 3/29

Daddy Dearest *

25. 4/1

Bob Trevino Likes It B-

26. 4/3

A Minecraft Movie B

27. 4/10

A Nice Indian Boy A-

28. 4/11

The Amateur B

29. 4/12

The Ballad of Wallace Island B

30. 4/14

Drop B-

31. 4/21

The wedding Banquet B+

32. 4/22

Sinners B+

33. 5/6

Thunderbolts* B

34. 5/7

The Accountant 2 C+

35. 5/13

Fight or Flight B

36. 5/15

Friendship B+

37. 5/20

Things Like This C

38. 5/22

Mission: Impossible - The Final Reckoning B+

39. 5/25

Twinless B+ **

40. 6/12

The Phoenician Scheme B

41. 6/13

Materialists A-

42. 6/15

How to Train Your Dragon B-

43. 6/18

Jane Austen Wrecked My Life B

44. 6/19

28 Years Later B

45. 6/20

Elio B-

46. 6/26

F1 B+

47. 6/30

M3GAN 2.0 B-

48. 7/3

Jurassic World: Rebirth B-

49. 7/10

Superman C+

50. 7/15

Sorry, Baby A

51. 7/17

Eddington B-

52. 7/29

Oh, Hi! B-

53. 7/30

The Fantastic Four: First Steps B-

54. 8/2

The Naked Gun B+

55. 8/8

Weapons A-

56. 8/18

Nobody 2 C+

57. 8/23

Honey Don't B

58. 8/28

Caught Stealing B+

59. 9/1

The Roses B-

60. 9/11

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale B

61. 9/12

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues B

62. 9/13

The Long Walk B-

63. 9/20

The History of Sound A-

64. 9/21

The Baltimorons B+

65. 9/26

One Battle After Another A

66. 9/28

Eleanor the Great B

67. 10/3

Anemone B

68. 10/4

The Lost Bus B+ ***

69. 10/8

Are We Good? B

70. 10/9

By Design (

B-) /

The Sale (

B) /

Yakshi (

B+) ****

71. 10/10

Tron: Ares C+

72. 10/12

Roofman B-

73. 10/14

Kiss of the Spider Woman B

74. 10/17

After the Hunt B-

75. 10/18

Good Fortune C+

76. 10/23

The Mastermind C+

77. 10/24

Blue Moon B

78. 10/25

Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere B-

79. 10/26

If I Had Legs I'd Kick You A-

80. 10/28

A House of Dynamite B+ ***

81. 11/2

Bugonia B+

82. 11/4

It Was Just an Accident A-

83. 11/8

Die My Love B

84. 11/9

Predator: Badlands B

85. 11/11

Frankenstein B- ***

86. 11/13

The Running Man C

87. 11/20

Wicked: For Good B

88. 11/21

Train Dreams A- ***

89. 11/23

Sentimental Value A-

90. 11/24

Sisu: Road to Revenge B

91. 11/26

Eternity B

92. 11/29

Hamnet A-

93. 12/1

Rental Family B-

94. 12/3

Zootopia 2 B

95. 12/9

Jay Kelly B ***

96. 12/12

Wake Up Dead Man: A Knives Out Mystery B+ ***

97. 12/15

Dust Bunny B+

98. 12/21

Avarar: Fire and Ash B

99. 12/27

Marty Supreme B+

100. 12/30

Anaconda C+

* Re-issue (no new review, or no full review)

** SIFF advanced screening

*** Viewed streaming at home

**** Tasveer South Asian Film Festival

10. Hard Truths A-

10. Hard Truths A-

9. Weapons A-

9. Weapons A-

8. Black Bag A-

8. Black Bag A-

7. I'm Still Here A-

7. I'm Still Here A-

6. Sentimental Value A-

6. Sentimental Value A-

5. The History of Sound A-

5. The History of Sound A-

4. The Seed of the Sacred Fig A-

4. The Seed of the Sacred Fig A-

3. If I Had Legs I'd Kick You A-

It's difficult to put into words just how much I loved If I Had Legs I'd Kick You, given by definitive inability to relate: this is about a woman who feels so unqualified as a mother, taking care of child with a debilitating medical condition and feeling so overwhelmed by it all that she makes a succession of wildly irresponsible choices. But it's a credit to Rose Byrne's extraordinary performance as Linda that I felt sympathy for this character, in a film easily compared to

3. If I Had Legs I'd Kick You A-

It's difficult to put into words just how much I loved If I Had Legs I'd Kick You, given by definitive inability to relate: this is about a woman who feels so unqualified as a mother, taking care of child with a debilitating medical condition and feeling so overwhelmed by it all that she makes a succession of wildly irresponsible choices. But it's a credit to Rose Byrne's extraordinary performance as Linda that I felt sympathy for this character, in a film easily compared to  2. Sorry, Baby A

2. Sorry, Baby A

1. One Battle After Another A

1. One Battle After Another A

5. Nobody 2 C+

5. Nobody 2 C+

4. Tron: Ares C+

4. Tron: Ares C+

3. The Running Man C

3. The Running Man C

2. Things Like This C

2. Things Like This C

1. Love Hurts D+

1. Love Hurts D+